Mixed Messages - The Forward Stroke

Periodically I enjoy sharing some thoughts with you and just when I’m thinking of a topic, something like this ‘Pings’ up on social media and instead of their being an outcry of, ‘You don’t paddle like that!’ like lambs to the slaughter, there’s an acceptance this must surely have been handed down by divine intervention, perhaps the musing of primitive man scratched onto a cave wall on the northern shores of Nuku Hiva, the epiphany you’ve been searching for.

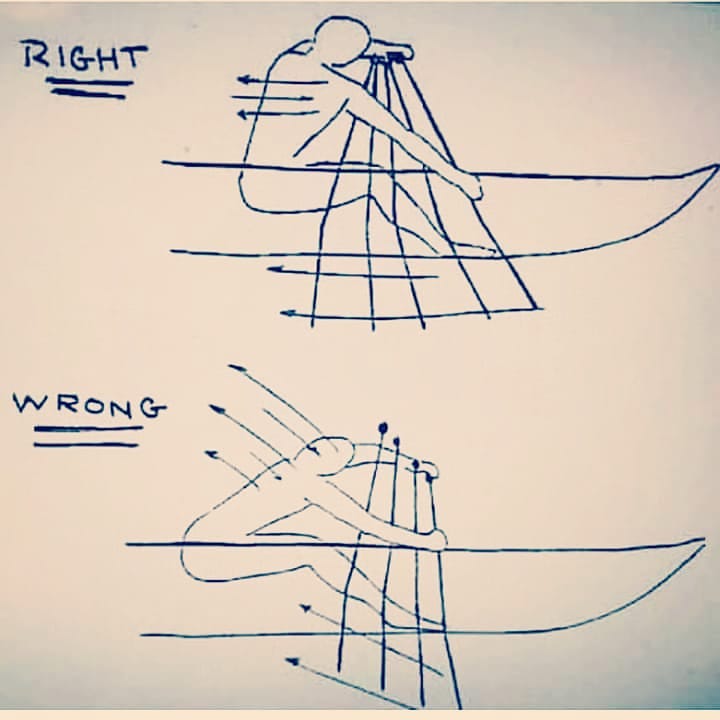

Well, sorry to be the bearer of bad news, but these simplified sketches fail to tell the whole story and ironically, if you were to blend them together, keeping the good, discarding the bad, you may be close to finding some clarity.

Keep in mind these illustrations allude to the blade moving through the water, when in fact it should remain near stationary (anchored) as you pull yourself up to it; therefore these images are misleading in relation to what is really going on, but like you, I understand the message attempting to be presented.

Let’s Address Mr Right.

In the first instance you’re going to assume ‘I must paddle with my elbow locked and hyperextended, apply no downward energy and be robotic in my movements’. In short, if you paddled in this way, you fall on the extreme side of ‘Static Paddling’ where there is minimal upper or lower body movement. Yes, this is a real-life terminology the opposite of which is ‘Dynamic’.

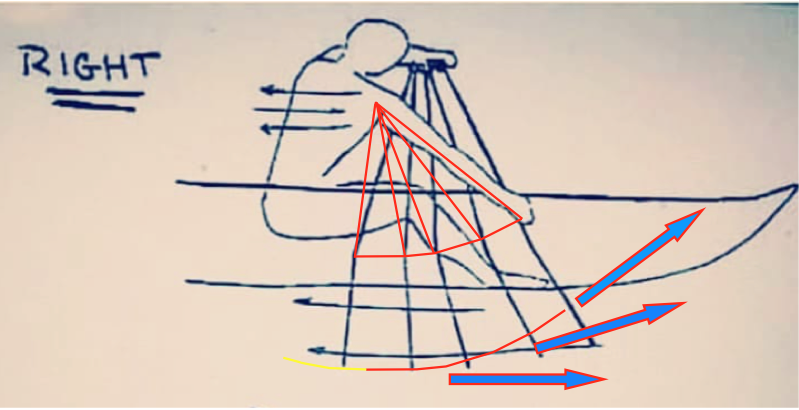

The idea of paddling with a leading arm more or less ‘locked’ at the elbow (hyper-extended) will guarantee as you unwind your torso through the stroke, the blade will follow quite a different path than shown. It will in fact take a deep crescent pathway and stall rapidly after its ‘vertical moment’.

Additionally, your top hand naturally wants to travel in a downward and traverse manner across the body line. In fact if it doesn’t, nothing much is going to happen in respect of ‘power’ and the blade will travel away from the side of the canoe. This further contributes to driving the blade ever deeper throughout the power phase.

The more likely pathway in relation to the Centre of Effort of the blade.

In this respect Mr Right, fails to show what really happens below the water line in relation to the anatomical pathway of your shoulder and arm and how this relates to the pathway of the paddle. Additionally you are reliant almost entirely on body rotation (torque).

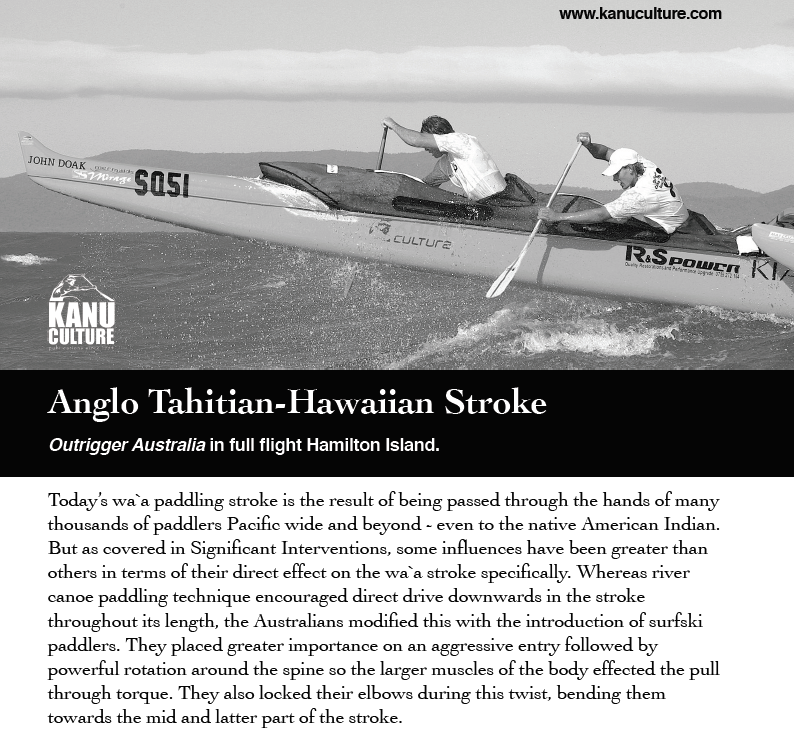

That aside, what seems to be illustrated here is perhaps an attempt to replicate the so-called ‘Tahitian Stroke’ a name which in itself is a misnomer and a poor nomenclature for a stroke which is merely a hybrid of all that has gone before it, whether Australian, Californian, Hawaiian, Tahitian and everything in between for example.

1995. Any idea ‘Mr Right’ is a new approach is ‘Wrong’. http://kanuculture.com/intro

Dynamic and Static paddling technique is a real thing and each with its merits depending on the individual and one of the challenges in putting a crew together to be either all Static or Dynamic which permits greater uniformity, but not always possible so the blend has to be considered carefully.

Again this is old news, the only caveat I should mention is that although the elbow was locked it was more accurately, ‘locked and cocked’.

If this is the case, there’s one continual detail overlooked if that’s part of the intention - and there is NO excuse for it unless you live under a rock.

TAHITIANS USE DOUBLE BEND PADDLES not single bend.

It matters a lot, as it affects the relationship of the top arm in relation to the shoulder as the upper bend puts the grip further back, while the lower bend provides added reach out front for less need to over extend yourself. The top arm can be ‘cocked’ further back and it promotes rotation of the torso more effectively.

Paddling with ‘Rigor’ (as in rigor mortis) versus that of ‘Vigor' - is also promoted for SUP with illustrations not dissimilar. Not unexpectedly, SUP paddlers around the world have looked at this snap shot of ‘How to paddle’ without being told this is simply phase 1 (the Set Up) of 5, 6 or 9 phases depending how you want to break it down and consequently go on to paddle literally in this robotic, static, rigor-mortis like manner.

Lower arm hyperextended, lack of rotation, offside leg locked and so on. With the arm remaining like this, the path of the paddle is doomed to be downward, then very soon after, upward with virtually no ‘moment’ spent in the vertical when the blade is offering up the biggest resistance and propulsion in the direction of travel you want - forward.

This above illustration was drawn when the sport more less gained traction and is now one of a number of holy grail illustrations alluding to perfect form to be maintained throughout the stroke and you wonder why most SUP paddlers look like robotic kooks, with stiff arms, stiff legs, locked ankles and so on and paddle as if attempting to dig a hole.

Taken from Stand Up Paddle A Paddlers Guide book - part of many pages and illustrations very much more detailed http://kanuculture.com/stand-up-paddle-boarding-book

Mr Wrong

If Mr Right can be deemed ‘Static’ then Mr Wrong ‘Dynamic’ - and it’s not all bad news save for the fact that the upper body, in its entirety, is being shown to be thrusting upwards then presumably downwards towards the gunnel, which we know to be ‘Bobbing’ - which, ironically is a technique used on occasion when paddling downwind when riding bumps.

Essentially, pumping the body in this way, provides inertia downwards and forwards into the canoe and therefore it’s questionable as to what degree you should eliminate it all together or more’s the point, how to add it into the equation efficiently.

Knowing this iterates the point that it legitimately provides forward thrust even if there is some downward. The idea you swing your paddle and all but negate any downward drive, let alone energy into the set up, entry and catch phase and rely upon ‘twist with locked arms’ only, is a complete misrepresentation of what needs to happen. Additionally there is always the reality, the good entry and catch, will lead to ‘lift’ from the momentum pull is initiated which helps negate some drive downward from body weight.

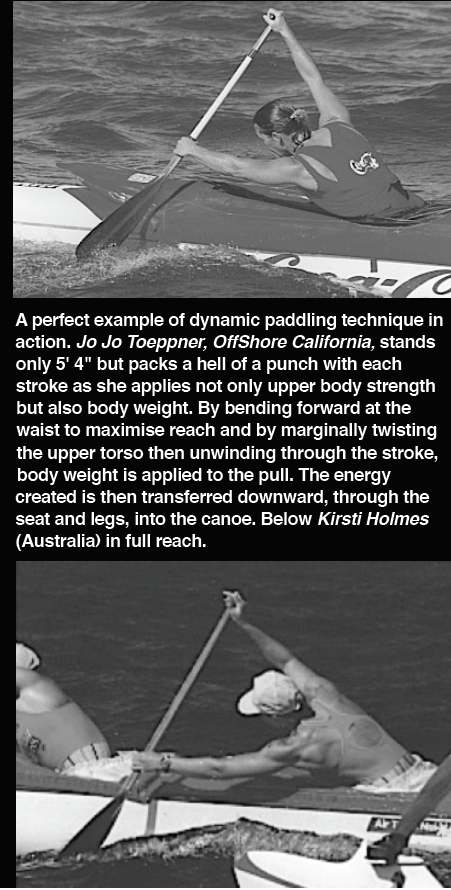

Another consideration is that Mr Right, is unwittingly, misogynistic. It has long been accepted that lighter weight women (small framed) including men, should adopt a more dynamic style of paddling in order to apply body weight effectively into - and more importantly ‘over’ the stroke. This approach is not something that has now been stripped from the ‘how to technical manuals’ - it’s a legitimate way to compensate for some degree of a lack of physicality.

OK so this is old school for sure - however it serves to put emphasis on paddling in a dynamic style that is not without merit. http://kanuculture.com/intro

Returning to Mr Wrong, with somewhat less lean into the stroke, loading up the front foot, so as to rotate around the spine, dropping only from the shoulder, with the body angled as a result of rotating, this would negate ‘Bobbing’ and result in sufficient energy downward to the blade to initiate ‘lift’, add some forward momentum and set up a better likelihood of a solid catch.

You cannot paddle with a lack of dynamism and expect to gain enough traction in the water or impetus to actually achieve much on return of effort - you have to put in, in order to get out.

So far as the trajectory of the blade is concerned, Mr Wrongs blade is illustrated as entering too deep and following an angled upward trend so as to pull the canoe down - however as mentioned, the blade should remain stationary and so long as body rotation is applied as aforementioned, eliminating ‘Bobbing’ - while applying a degree of elbow bend, this would be eliminated.

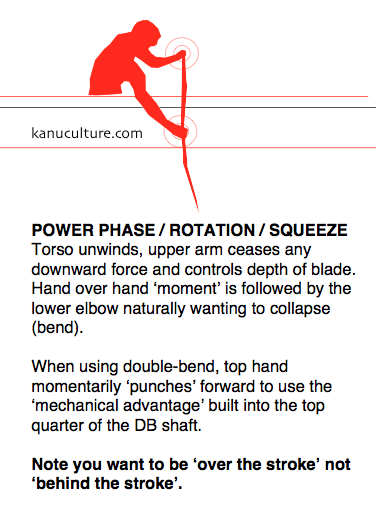

When you consider the lower arm, calmly and logically - deep breath, if the elbow is permitted to bend, then the blade stands a great chance in remaining vertical for longer.

THE TAHITIAN FACTOR

There’s a worrisome trend leaning towards the idea we should all ‘Paddle like a Tahitian’ which presumes a long list of caveats . The focus is centred entirely upon an elite group of male athletes of supreme natural ability and DNA hard wired for the task at hand. They exclusively use double bend paddles and have mastered this tool, not because of its ergonomics but because of its mechanical advantages.

The merits, break down and analyse of the forward stroke and the recent obsession with the inappropriately named ‘Tahitian’ stroke, could well be doing more harm than good as interpreters attempt to come to grips with how to emulate it.

Without exception and worryingly, the entire process of analysis, stems from analysing predominantly elite, male, Tahitian crews, while failing to account for or stress the need to make use of double bends (using Tahitian constructed paddles) and making the wrongful assumption, this form, style and technique, suits female crews and all-commers verbatim.

In this case ‘Monkey See, Monkey Do’ is not necessarily the way to go, not withstanding all other merits and factors that make Tahitians fast; there’s a bunch of reasons from their DNA, culture, environment and factors beyond the reach of the likes of me, you and most of us.