Concurring with the King

My first visit to Tahiti was in ’97 my last in ’17, a total of some 20 voyages of discovery and counting. Ever since the late Tommy Holmes documented in his 1981 book, ‘The Hawaiian Canoe’ stark differences between Hawaiian and Tahitian techniques, citing high stroke rates, an aggressive shorter reach and more besides, a fascination for Tahitian speed and efficiency has continued. I have written extensively of the Tahitian ‘way’ whether paddling rudderless V1 or V6, noting their use of the double bend paddle and the application thereof and not for the nonsense spoken about wrist angles, but more for the mechanical advantages they provide.

Refreshingly, I have been watching, listening and following Tupuria King and whether he knows it or not, we are connected through luminaries such as the late Kris Kjeldsen and his son Maui Kjeldsen and the late Bo Herbert of Nga Hoe Horo. He was introduced to waka ama (OC) by his father David King from the moment he was born and his life has since come to revolve around the sport with considerable competitive success. He’s a breath of fresh air, because IMO, he gets it - I concur with the way he thinks and of what he speaks, delivering solid, insightful knowledge.

Above is a shortened version overview of what is being covered in this blog post.

Tahitians have been paddling uniquely differently for as long as anyone can remember. In 1975 two Tahitian crews including ‘Maire Nui’ (founded in 1948) entered the Molokai Hoe for the first time, finishing 2nd. Their technique was identified as uniquely different and from here the fascination began.

TAHITI 1988 - (@ 1.35 seconds) take note of single bend paddles made from hau (mangrove) wide blades, but relatively short lengths. Tahitians moved to using double bends by the mid 90s - though the Vahine crews took longer to make the change - and it’s speculative if women are suited to double bends.

Paddlers are leaning forwards to gain reach and stay forward.

Minimal or no sit up limiting body movement which is desirable due to LOW FREEBOARD design of the va’a to avoid swamping.

Bent top arm to assist reach and bring shoulders and chest more in to play without the need to twist excessively and the ability to get over the stroke, also note a bent lower arm pulling parallel.

Limited twist - a circular stroke, relying on the arms - top pushing down, then forwards, lower pulling - early exit and relatively high stroke rates.

Meanwhile in Australia during the late 80s, crews were developing their interpretation, with a stroke rate faster even than that of Tahitian crews of the time, in addition to greater rotation around the spine (torque) brought in from Surf Ski paddling. In ’91, two Aussie crews finished 1st and 2nd at the Molokai Hoe. Outrigger Australia took lin honours, followed by Panamuna OCC who subsequently went on to win in ’92.

From this moment onwards, the ground rules were changed in respect of sheer fitness and professionalism so much so, the Hawaiian paddling community could sense their national team sport was under threat of being usurped by a new breed. The commonality for these relatively inexperienced part time OC paddlers, was that the crew were made up of professional and semi-professional multi-disciplinary watermen, possessing elite surfski and kayaking abilities and levels of fitness.

Fast forward to today and Tahitian crews have come to dominate the Molokai Hoe for the best part of the last 15 years. Fascination with just how they paddle, remains omnipresent. With lock down nurturing a proliferation of ‘How to’ videos, there are many willing viewers thirsting for knowledge and so too, I have been watching to see what aligns with my personal experience and research and I have to say, the conflicting information can make for perplexing viewing.

Historically speaking, ever since Hawaii has had to endure the onslaught of off-island crews attending the Molokai Hoe and Na Wahine O Ke Kai since the mid 70s, be it from Tahiti, mainland USA, Australia or New Zealand, Hawaiian’s have struggled to adapt to change due to traditional dogma, when other regions were simply focused on going fast and indeed winning in Hawaii and they have done so in spectacular form. You cannot help sense some level of exasperation that has emanated from Hawaii over this dilemma and in the rush to adapt I worry they may be getting some wires crossed.

Training Videos

It’s one thing to watch a bunch of training videos from Shell, EDT, OPT or any number of other crews, but quite another to be there and watch them race or to even paddle with them.

They practice all manner of stroke techniques from fast, short and light, to long, slow and strong and use long exits at times for active recovery or perhaps on longer downwind rides, but for the most part it remains all about the catch and working the stroke up front - in this respect not much for them has changed for many years.

The tahitian pukea stroke?

Oahu based coached John Puakea, has in recent years offered interpretations of the Tahitian stroke and this can be seen in any number of video demonstrations and explanations, where he is either offering up the information or being interviewed.

However, I cannot but help notice elements seem to have been lost in translation or at least, interpretation and slap in the face of all I (and others) have ever known or have seen when at the coal face watching these crews. Add to this the fact, few seem eager to point this out let alone challenge it - meanwhile his way of thinking is being viewed in the thousands!

Let’s get one think rock solid crystal clear. When paddlers in Hawaii start referring to the Tahitian ‘Pukea’ Outrigger Canoe Stroke, then all common sense has just left the building and jingoism just arrived sliding in sideways. Respectfully, John Pukea has zilch, nada, nothing to do with the evolution of the Tahitian stroke, which if not by geographic proximity alone, smacks in the face of respect for the Tahitian way of things. So why am I hearing this - and I don’t believe John has anything to do with this nomenclature - but groupies might . . . furthermore if it’s because you think he deciphered the stroke, think again, this has been going on since the mid 1970s.

In this example of the set up, entry and catch, you will see

Top and lower arm straight at the set up

Minimal body rotation

Entry initiated with emphasis on simply lowering both arms to plant the blade.

Little suggestion of body weight or lowering of a leading shoulder

Suggests negated body weight over the stroke

Apparent lack of dynamism on entry required

No weight transfer in cementing the catch.

It’s not enough to simply ‘bury’ the blade, being as ‘speed and power’ prevent water leaving the blade face prematurely, therefore you need a degree of explosive power to make this work.

Key points from the clip

Let your arms ‘put’ the paddle in the water

I want to make sure when I enter, I am not coming back (pulling)

Come forward and set the blade and do not pull too soon

The arms ‘put’ the paddle in - not the body

You only want a little pressure on the top hand”

We can all agree not to pull air before pulling water, but it’s all a matter of how you enter the blade. If you swing in from the recovery and knife edge the blade in angled slightly sideways, downward force can be applied early, resulting in minimal air down-take and an early on set of lift and pull.

Additionally, ‘putting’ or ‘placing’ the blade in the water as described, suggests a lacks of commitment on the part of the paddler? Pressure from the top hand is a key component - a ‘little pressure’ seems to down-play an integral part of the mechanics.

At the very least, at the point of ‘set up’ (the apex of the recovery) - you need to be ‘coiled’ and ready to enter the blade with some level of energy and pressure - simply lowering the arms is not enough. Entry and catch need be like a small explosion of energy. If the blade is placed nonchalantly, the progressive stages of the catch will die a natural death and result in water simply spilling away from the blade face like a knife through butter.

Key points from the clip

You never want to bend your (top) arm back to get reach

It’s not a matter of bending the top arm to gain added reach (which you do) but just as much about the added bio-mechanical advantages in doing so?

If you bend it back, you’re giving it somewhere to go and that’s a bad motion

So far as where your top hand goes, you control it to go downwards and transversely, so this is problem that does not exist so long as you control the trajectory?

Start with a straight top arm, you have a lot of power and pressure from your lat.

It’s the opposite Lat’ that does the pulling? Compression from the top arm comes from the shoulder, trap, arm and only some from the lat’?

You want to cement the paddle before pulling

The reality of burying your blade fully before pulling, it’s counter-intuitive and not possible in a literal sense, because as mysterious a thing as the catch is, it’s part of dynamic moving process; as entry is being made the catch is also being created and so too, lift is brought about initiating forward motion - if you wait to fully immerse the blade before any form of active pulling - it’s too late.

(See Tupuria’s comments below)Whatever happened to ‘reach’ being at least moderately important

And what of some discernible amount of rotation (wind up) into the stroke

Where’s the early exit

How low (slow) would stroke rates be if labouring the stroke in this way at the back of the stroke.

In fairness, demonstrating in a tank is not the best, being as you are stationary, however, consider when the canoe is moving, you have to ‘accelerate’ the blade in order to have any form of quality catch so as to be faster than that of the canoe’s rate of travel.

Note also how low the top hand travels down and back over and along the gunnel? The top hand should be mixing porridge, stirring stew on the stove and works anti-clockwise between forehead and about a half to two thirds of the distance down your torso - not down to the gunnel.

Tahitian crews with long exits

If you see Tahitian crews lengthening the exit, don’t go thinking this is how they paddle all the time or that they are continuing to ‘pull down’.

They sometimes use this as ‘Active Recovery’ and a re-set, by reducing the stroke rate and will sometimes use in long flat sections of water, common to Tahiti; rarely during a Molokai crossing, where the stroke remains more about attacking the stroke up front.

Below - Tahiti Nui Va’a just 4 years ago . . . bent top arms, aggressive placement, long reach, no long exaggerated exit, early pull even before full immersion of blade . . .

The top arm

Cocking the top arm back, elbow down, is akin to preparing to throw a spear, or a rock and has sound bio-mechanical principles.

It ensures the top shoulder and chest are engaged from the moment entry is initiated. It ensure the chest is open, not closed and creates a bigger wider triangulation encouraging core muscle activation and torque.

Its task is to ‘push’ downwards, then transversely, not forwards as feared. This is easily taught and learned. Try throwing a spear or a rock with no wind-up and a straight arm - it won't end well.

The top arm also dictates the travel of the blade, in relation to the side of the canoe, being at the upper extremity of the tool you hold in your hand, the extremity of which is the blade tip.

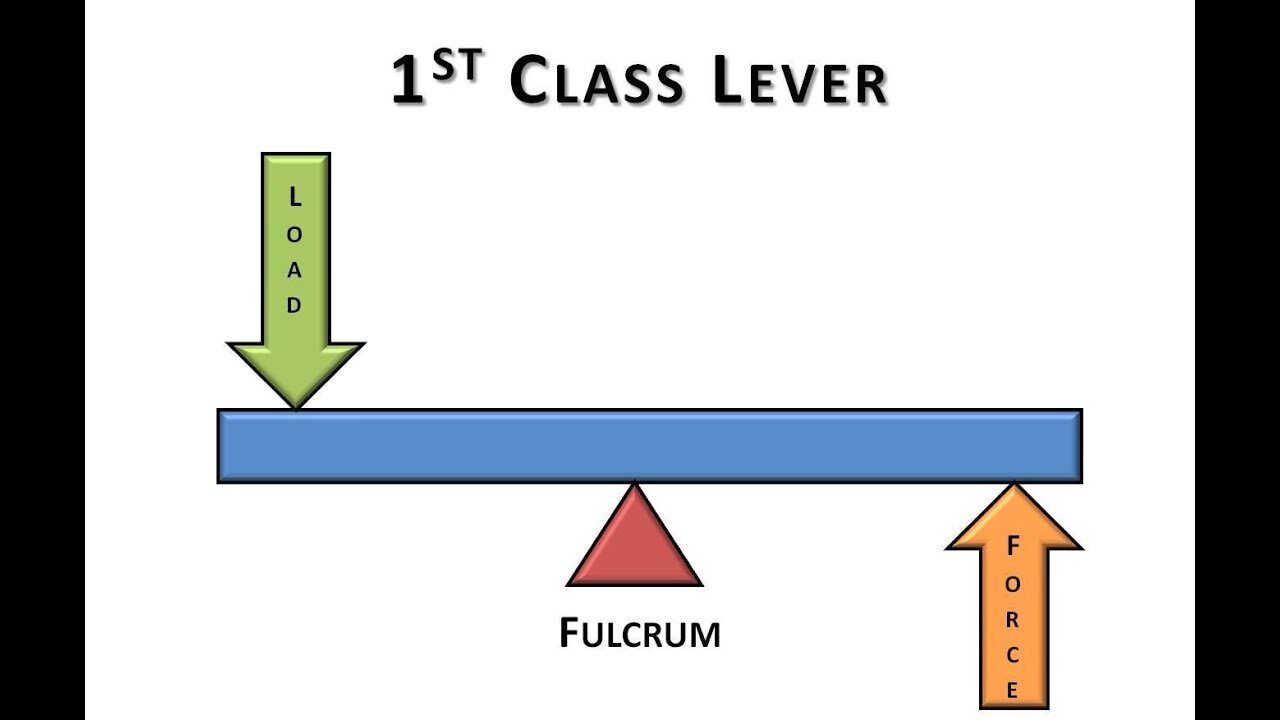

The world of levers

While the paddle acts certainly as a lever of a type, which type, has long been a conundrum, as we are dealing with water and the fragility of being human.

In the final analysis we cannot apply 1st or 2nd class lever applications in the full sense of the word, merely something approximating a mix of both.

In fact since the 80s, canoe paddling moved to eliminate pushing forward with the top arm which assumes 1st class lever principles, opting for greater body torque and rotation with emphasis on slowing the rate of travel angle of the blade from positive, to neutral, to negative incline.

This acknowledges that as good as a canoe paddle may be as a lever, ‘we’ are poor core components of the levering process, in terms of being a fulcrum or in terms of pulling or pushing.

The distance between the lower hand and the centre of effort of the blade can be considered as the lower lever arm length.

Pushing forwards with the top arm throughout the process, with the lower doing little more than acting as a fulcrum, would be to attempt to use the paddle as a 1st class lever, which might make sense - but it doesn’t because the lower hand is a non-fixed fulcrum point and therefore utterly inefficient.

Where ‘load’ equals top hand pushing - and the ‘fulcrum’ the lower hand remaining stationary acting as as a (non) fixed fulcrum and ‘force’ being the resulting pull / pressure at the blade face.

Where ‘fulcrum’ equals the blade face at the ‘catch’ and ‘load’ being pull from the lower hand and ‘force’ being push from the top hand

On the other hand if we consider the fulcrum point to be the blade, if it can be ‘cemented’ during the catch, then we are moving more towards a 2nd class lever. But this too has limitations, because the fulcrum in this instance (the blade) moves - or at least pivots around its centre of effort and is only briefly vertical.

Altered realities

Meanwhile down under in New Zealand, Tupuria King, one of the countries best, intrinsically linked to the Tahitian way of thinking, actively rejects John’s reality and substitutes it for his own, advocating top arm cocked back, elbow down, lower arm straight and a falling forwards and downwards to bring about the entry and catch assisted by body weight, which in turns sets in motion lift, forward propulsion and indeed brings about the catch quicker. I concur.

Compare Tupu’s notes on the set up and entry with that of John’s.

They are polar opposites

Tupuria gives ‘thoughts with facts’ not just the idea of your top arm has a bad place to go? His reasoning is sound and hard to challenge and makes good sense.

Below Tupuria again stresses the importance of reach, cocked top arm and how he goes about the entry by falling on the paddle . . .

Key points from the clip

I don’t believe I have to set the paddle before I pull back

I initiate the catch with the power of my body weight

I initiate the catch by falling on my paddle

One of the ways to improve adding body weight to the stroke is via the top arm

I don’t agree with coaches teaching paddlers to maintain a really straight top arm

A straight top arms prevents putting downward power to the blade

Bend in the top arm improves the positive angle of the blade (reach + lift)

The upper shoulder and chest can contribute to a stronger catch in this way

As soon as the blade enters the water I initiate lift then forward motion

When pulling (rotating) the upper arm continues to push downward (and across)

The lower arm will break / bend towards the back of the stroke.

It’s difficult to pick holes in any of what’s said here or demonstrated and he’s not backward in coming forward to say he does not agree with dual, straight arm paddling . It’s from this point you will see that Tupuria King and indeed my own beliefs align.

In respect of a top bent arm with elbow down, this in fact engages the shoulder and chest rather than isolate them and sets it up better to push down and across and to get over the stroke.

The top arm pushes downwards then transversely across the body line - not forwards, with the caveat that in the late 90s Tahitians added in a marginal push forward with cranked double-bends at the vertical phase of the blades travel.

(See also Tupuria’s comments below)As for the exit, when paddling with relatively straight lower arm at entry, it will naturally want to ‘break’ (bend) once the blade is past vertical and this therefore should be allowed to naturally occur, the exit following on soon after.

Note: For V1 you need maintain your centre of gravity / body, over the centre of buoyancy of the va’a, minimising leaning forward to avoid upsetting directional stability. Additionally, you will often have a long exit because of the position of the canoe on a wave or because of steering strokes used.

An example of how with cocked upper arm, reach is improved as against straightening the top arm out in front of you. Additionally the opposing side is opened up (wound-up) ready to unwind and deliver torque to the blade in keeping with avoiding using the paddle as a 1st or 2nd class lever, but somewhere in between in working with non-fixed fulcrum points of either the lower hand or that of the blade.

Cocked top arm engages the top shoulder and chest and helps to open (twist) the torso in preparedness of engaging torque when winding through the stroke. Greater reach is achieved for less lean forward and simply falling forward to enter and initiate the catch becomes a smooth and natural process which provides impetus through actively adding body weight to the stroke. The top arm alignment and angle, pushes downwards, then transversely as the body unwinds. Emphasis here is on smooth use of body weight and use of torque through rotation.

Conversely, with top arm straight, the top shoulder is somewhat isolated, the chest not opened and reach is severely reduced as will be the lift component of the stroke on account of the angle of the blade at entry. Torque is also compromised being as the body is not wound-up so it cannot unwind with any degree of power. Simply ‘putting’ the blade into the water by lowering the arms, not the body, negates weight and impetus. The focus here appears to be greater use of the arms and less of the body, both in terms of entry or indeed use of torque.

This technique as demonstrated by Tupuria for the set up, entry and catch, I have advocated for as long as I can remember and therefore I find myself siding with myself and with Mr King - long live the King!

Tupuria King - NEXT LEVEL TRAINING